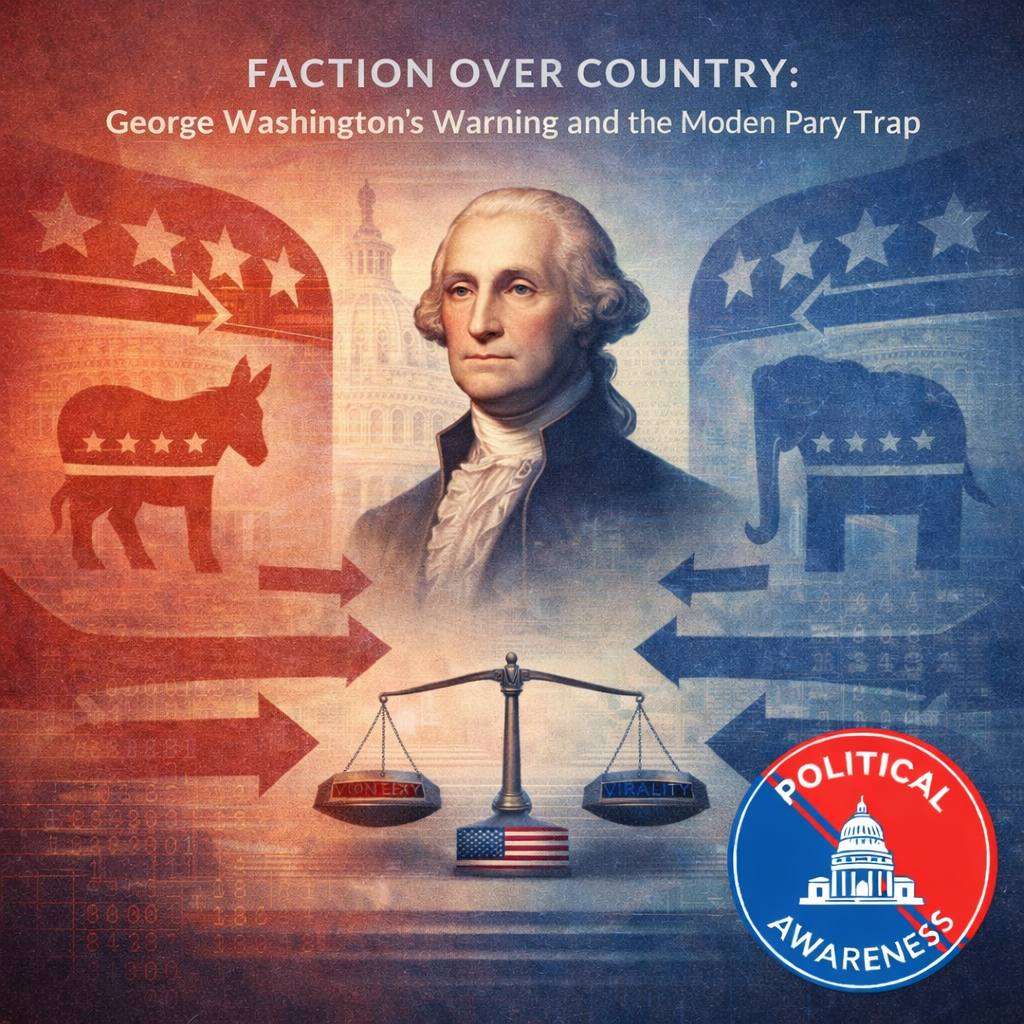

Faction Over Country: George Washington’s Warning and the Modern Party Trap

EDITOR’S NOTE

Every democracy relies on disagreement. Competing ideas, contested priorities, and sharp debates are not weaknesses of a free system—they are evidence of its health. Yet history shows that democracies rarely collapse from disagreement alone. They erode when disagreement hardens into identity, when loyalty replaces judgment, and when political affiliation becomes a substitute for civic responsibility.

In his Farewell Address, George Washington warned that political parties—what he called “factions”—could one day redirect allegiance away from the nation itself. More than two centuries later, that warning no longer reads as abstract theory. This feature examines the structural risks of party loyalty in modern American politics, why those risks intensify during moments of institutional stress, and what democratic accountability requires when loyalty and law come into conflict.

Note: Political Awareness never authorizes its published communication on behalf of any candidate or their committees.

Washington’s Fear Was Structural, Not Personal

George Washington did not oppose disagreement. He opposed displacement of allegiance.

In his 1796 Farewell Address, Washington cautioned that political factions would eventually “enfeeble the public administration” and open the door for ambition, corruption, and foreign influence. Importantly, he did not argue that parties would be immoral or that their members would be malicious. His concern was structural: factions, once entrenched, would demand loyalty not to constitutional principles but to partisan identity.

Washington understood something that modern political science would later formalize—systems shape behavior. Once political identity becomes tribal, dissent becomes betrayal. Evidence becomes negotiable. Leaders are judged not by standards, but by alignment.

This concern was not partisan in origin, nor was it limited to any ideology. Washington warned against the mechanism itself.

How Party Systems Changed From Vehicles to Identities

Political parties did not emerge in the United States as permanent institutions. Early parties formed as loose coalitions around specific issues—banking, federal power, foreign alignment. They were tools, not identities.

Over time, however, several developments transformed parties into something far more durable:

- Ballot access laws that favored established parties

- Primary systems that rewarded ideological purity

- Media ecosystems that framed politics as binary conflict

- Fundraising structures that punished intra-party dissent

Together, these forces reshaped parties from vehicles of representation into identity containers. Once inside, members faced strong incentives to defend the party’s leaders regardless of conduct, because attacking leadership threatened the collective identity itself.

This is the condition Washington feared: when loyalty becomes defensive rather than evaluative.

When Evidence Loses Its Power

One of the most destabilizing effects of hardened party identity is the erosion of evidence as a shared currency.

In healthy democratic systems, facts do not guarantee agreement—but they anchor debate. When evidence becomes filtered through partisan loyalty, however, it no longer persuades. It merely signals affiliation.

This dynamic explains why modern political scandals often fail to produce institutional rupture. Facts that would once have triggered investigations, resignations, or reforms now generate

polarization instead. Each side evaluates not the conduct, but the implications for the party’s power.

The result is not ignorance. It is motivated dismissal—a rational response within a system that treats loyalty as survival.

Leadership, Norms, and the Cost of Silence

Democracies depend on more than laws. They depend on norms—unwritten expectations that constrain behavior even when formal rules permit abuse.

When leaders repeatedly test those norms, democratic systems rely on internal correction: colleagues, institutions, and parties enforcing boundaries before courts or crises are required.

Party systems, however, weaken that corrective function. Speaking out against one’s own leader risks primary challenges, donor withdrawal, media backlash, and social exile. Silence becomes safer than dissent, even when conduct raises serious legal or ethical concerns.

This is not unique to any party. It is a predictable outcome of identity-based politics.

The question Political Awareness asks is not why individuals remain silent, but why the system rewards silence at all.

The Personalization of Power

Another risk Washington anticipated was the personalization of power—when loyalty shifts from principles to individuals.

Modern party structures amplify this risk. Charismatic leaders can become symbolic stand-ins for the party itself, making criticism of leadership indistinguishable from betrayal of the group. Once this occurs, accountability mechanisms falter.

The problem is not that voters or officials lack intelligence or morality. It is that systems designed around permanent competition encourage defensive alignment over deliberation.

In such systems, democratic decay does not require overt authoritarianism. It advances quietly through accommodation.

Democracy Does Not Fail All at Once

One of the most persistent myths about democratic collapse is that it arrives suddenly—through coups, revolutions, or constitutional suspension. In reality, modern democracies more often erode incrementally.

Key warning signs include:

- Normalization of rule-breaking

- Dismissal of oversight as partisan harassment

- Selective enforcement of standards

- Delegitimization of neutral institutions

None of these steps alone destroys democracy. Together, they create a system in which accountability becomes optional for those with sufficient loyalty.

Washington’s warning was not about chaos. It was about drift.

The Role of Citizens in a Party-Dominated System

Political Awareness places responsibility not only on institutions, but on citizens.

In a party-dominated environment, citizenship requires more than voting. It requires evaluative independence—the willingness to judge actions by democratic standards even when doing so discomforts one’s political allies.

This does not require abandoning beliefs or pretending moral equivalence between all actors. It requires recognizing that democracy is not protected by outcomes, but by process.

When citizens excuse conduct, they would condemn in opponents, they reinforce the very factionalism Washington warned against.

DEMOCRATIC IMPLICATIONS

The central democratic risk examined here is not partisan victory or defeat. It is the replacement of constitutional loyalty with factional loyalty.

When parties become primary identity structures, they incentivize silence over scrutiny and allegiance over accountability. Over time, this weakens the guardrails that protect democratic systems from abuse—regardless of which party holds power.

Democracy survives disagreement. It does not survive the abandonment of standards.

FACT-CHECK & SOURCES

1. George Washington, Farewell Address (1796)

- S. Constitution and Federalist Papers (Madison, Hamilton, Jay)

- Levitsky & Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (Crown Publishing, 2018)

- Pew Research Center, Political Polarization Studies (2014–2024)

- Brookings Institution, Party Polarization and Democratic Norms

- Congressional Research Service, Party Leadership and Institutional Power

Leave a Reply